Edgar Jerins

Thu, May 15, 2008 at 4:20 PM in

Thu, May 15, 2008 at 4:20 PM in  Unwarranted Rants

Unwarranted Rants So I used to be a painter. If you're a painter you have painter friends. One of my painter friends is Edgar Jerins.

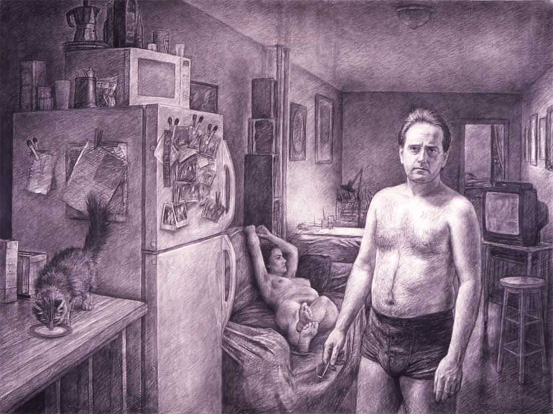

This is a drawing that Edger did of our buddy Steve and his girlfriend. (Steve's an artist too.)

This is a drawing that Edger did of our buddy Steve and his girlfriend. (Steve's an artist too.)

As an artist you often hear this: "I don't know art but I know what I like."

That's bullshit actually. If you knew about art, the art you like would drastically change. Saying that you don't know art but you know what you like is a complete manifestation and admittance that wallowing in ignorance is preferable to interest and knowledge. Here's what a critic said of Edgars work.

A recent show at the Tatistscheff Gallery in New York City (May 13–June 26) showed six works by Edgar Jerins that stretched the definition of drawing. There was nothing offhand or intimate about these huge charcoals on sheets of paper often measuring five-by-eight feet. The Nebraska-born artist describes these unsettling interior genre scenes as narrative portraits. The figures—friends and relatives, worked up from hundreds of photographs—are depicted in emotionally fraught domestic situations. Jerins admits to a special interest in the discontents of the middle-aged American male, as one title, The Artist’s Family, “We have to Move” (2004), suggests. Alienation is a venerable American theme, most notably embodied by Edward Hopper, but Jerins’s pictures are far more specific, moving toward Hitchcock gothic or storyboards for a documentary about the dysfunctional family. In Bill Prael, Wild Turkey Season (2003) a hunter dressed in camouflage stands with his gun, holding the hand of a little girl while two women—twins, one pregnant—slump stoically on the sofa. Cast shadows give the male ominous proportions as he towers above the room and its other occupants. You could easily imagine the scene as a Diane Arbus photograph, a comparison underlined by the choice of black and white. Jerins acknowledges that the pervasive atmosphere of despair and menace grows out of family history. Two of his brothers, both schizophrenics, committed suicide, using guns. Formally, the most striking aspects of his style are his attention to detail and his nourish flare for dramatic lighting. In Bill Prael, the magazines under the coffee table, the curios in a corner cabinet, the framed prints, the painstakingly delineated wood grain of the furniture, even the branches of the tree pressing at the window—all contribute to the sense of claustrophobia. Jerins has a strong sense of composition that holds things together. Kosmo, Charlie and Jack (2002) isolates its three protagonists architecturally. The deep perspective behind the adult suggests a past lived as least in part outside the walls. The deep perspective behind the adult suggests a past lived at least in part outside the walls. But the flanking boys are so introspective they seem trapped in private worlds. Their loneliness is underlined by the closed-off walls behind them and a tangle of wire casting spidery shadows, beneath the shell that supports a pile of stereo equipment. These are not easy works to look at, but their power is undeniable. On a scale that suggests nineteenth-century history painting Jerin’s drawings focus compulsively on the area of human experience that owes as much to psychoanalysis as it does to the tradition of socially conscious realism. Educated at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and now based in New York, Jerins is a 2004 recipient of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant. His work has been featured in surveys of contemporary figurative art at the Arnot Art Museum in Elmira, New York, and the Frye Art Museum in Seattle. The Tatistscheff Gallery is located at 529 West 20th Street, New York, New York, 10011. Telephone (212) 627-4527.

Reader Comments